There has been a steady increase in the number of individuals who undergo dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. The majority of these procedures are performed by nurse providers. The purpose of this study was to collect national data on the current practice among nursing providers within the American Society of Plastic Surgical Nurses (ASPSN). The goal was to utilize the national data and develop a document of the necessary competencies to guide the practice of providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. A survey tool was developed and validated for content by expert nursing providers among the membership of the ASPSN and disseminated via e-mail to the membership of the ASPSN. In addition, data from investigator training, mentoring, and evidence from a review of the literature were also incorporated into the competency document utilizing the Competency Outcomes and Performance Assessment(COPA) model. Common core issues became apparent that included contraindications for the use of botulinum toxin Type A and dermal fillers, postprocedure complications as well as strategies in terms of managing complications. The data also revealed that there is no common method providers are taught to assess the aesthetic patient and a lack of a collaborative relationship in current practice. Overwhelmingly, the respondents supported the need for defined practice competencies. A competency document to guide the practice of providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A has been developed for completion of this DNP project.

As a registered or advanced practice nurse, are you performing nonsurgical aesthetic enhancement procedures? What specific training did you undergo before initiating this area of specialty practice? How involved is your physician? Do you have competencies that guide your practice? Do you wonder if your practice is consistent with other providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections? Answers to these questions are imperative for the provider as well as for those individuals choosing to defy the aging process or enhance youth and beauty.

There is much attention in the media today about staying young and defying the aging process. We are each exposed to more than 2,000 advertisements a day, constituting perhaps the most powerful educational force in society (Kilbourne, 2006). The average American will spend 1.5 years of his or her life watching television commercials and advertisements sell a great deal more than products. Advertisements sell values, images, and concepts of success and worth (Kilbourne, 2006). From art to advertisements, every day we encounter images of beautiful and attractive people and manufacturers and industry have capitalized on this phenomenon. As the aging population demands to maintain youth and achieve beauty, the development of new, improved, and more refined aesthetic nonsurgical technologies, products, and procedures will continue to hit the market and remain enticing to potential consumers of all ages. Because of this extraordinary growth, there has been an influx of physicians and nonphysician providers into this highly challenging arena of practice.

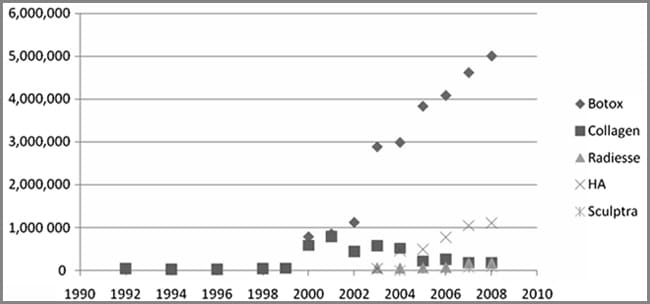

|

| Figure 1. The trends in the number of Botox (Botulinum toxin Typ e A) injections and dermal fillers from the American Society of Pla stic Surgeons database since 1992 to present. Note the rapid rise in both procedures since 2003 and 2004 and the steady decline in collagen injections with the introduction of other dermal filler produ cts including hyaluronic acid (HA). |

With the development and introduction of new products and technologies, the quest to defy the aging process and enhance beauty continues to this day. According to the 2008 Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics (American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 2009), there has been a steady increase in the number of consumers who have undergone nonsurgical aesthetic procedures including botulinum toxin Type A injections and dermal fillers and there appears to be no end in sight (see Figure 1). This phenomenon has required that healthcare providers adapt to these technical developments to meet the needs of the population, and has led to increased specialization in the area of plastic surgical nursing.

According to Jones (2009), the majority of these procedures are now performed by registered nurses, depending on the individual state’s scope of practice, under the direct supervision of physicians who are on site and physicians continue to delegate provision of these procedures to nonphysician providers (Jones, 2009). Presently, there are no specialty boards that regulate the practice of these nursing providers. The American Society of Plastic Surgical Nurses (ASPSN) offers certification for the plastic surgical nurse through the Plastic Surgical Nursing Certification Board. The Board believes that attainment of a common knowledge base, utilization of the nursing process, and a high level of skill in the practice setting are required for proficient practice in the specialty of plastic and reconstructive surgical nursing. Certification provides professional recognition for these achievements. The Board recognizes the value of education, administration, research, and clinical practice in fostering personal and professional growth (https://www.aspsn.org/certification.html). Although this examination is offered, it is global in the specialty of plastic surgical nursing and includes wounds, burns, pediatrics, and reconstruction as well as aesthetic nursing and does not focus on the practice of providing dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. As of yet, no widely accepted and utilized competency document for practice has been developed.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Competencies are defined as a set of knowledge, skills, traits, motives, and attitudes required for effective nursing practice and are specific to the particular area of focus (Zhang, Weety, Arthur, & Wong, 2000). As previously proposed, a review of the literature has highlighted the lack of widely accepted and utilized competencies to guide practice as a provider of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. However, a review of the literature on aesthetic medicine yielded one document claiming to identify competencies for providers practicing in aesthetic medicine. Aesthetic medicine describes the set of nonsurgical clinical procedures that aim to rejuvenate the dermis and reverse the signs of aging (Royal College of Nursing [RCN], 2005). In the United Kingdom, the RCN, in response to an increase in the number of nurses who wanted to practice in the field of aesthetic medicine, developed a competency framework aimed to guide nursing practice in the emerging specialty of aesthetic medicine (RCN, 2005). The RCN is the largest professional union for nursing in the United Kingdom, represents nurses and nursing, promotes excellence in practice, and shapes health policies in the United Kingdom and internationally (http://www.rcn.org.uk/). The framework utilized in the RCN document uses an outcomes competence model and identifies core competencies. Core competencies are defined as standard set of performance “domains” in which it is necessary to demonstrate proficiency to enter into professional practice (http://www.ehow.com/ list_6099114_core-competencies-nursing.html). Specialized skills that are unique to nursing providers in aesthetic medicine are outlined within these core competencies. The RCN document identified core competencies around which the specific competencies were centered. Development of this document was a joint effort among nurses, physicians, consultant surgeons, and organizations within the United Kingdom and is further acknowledged as not exhaustive or prescriptive but rather as a useful tool only to guide practice of aesthetic nursing providers (RCN, 2005).

During the last decade, major changes have become evident in the quality of patient care and safety in the United States and competence in clinical practice (Lenburg, Klein, Asdur-Rahman, Spencer, & Boyer, 2009). The drive for this current interest in competencies was the release in 1999 of the Institute of Medicine report “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System” Kohn, Corrigan, & Donaldson (2000). In spite of national initiatives to validate clinical competence, Lenburg (2008) identified problems relating to the promotion of competence as a result of limitations or the absence of a cohesive conceptual framework that supports assessment methods focused on practice competencies. Lenburg (1999) developed the Competency Outcomes Performance Assessment (COPA) Model in the early 1990s as a method to validate outcomes. The COPA Model is designed and structured as a theoretical framework to promote competence for practice. The model is based on the philosophy of competency-based, practice-oriented methods and outcomes and is organized around four essential conceptual pillars: (1) the specification of essential core practice competencies; (2) end-result competency outcomes; (3) practice-driven, interactive learning strategies; and (4) objective competency performance. Implementation of the model requires that four fundamental questions be resolved: (1) what are the essential competencies and outcomes for contemporary practice? (2) what are the indicators that define those competencies? (3) what are the most effective ways to learn those competencies? and (4) what are the most effective ways to document that practitioners have achieved the required competencies? (Lenburg, 1999).

The first of the four guiding questions may be addressed by identifying the required competencies and wording them as practice-based competency outcomes (Lenburg, 1999). In the COPA Model, eight core competencies are identified under which a flexible array of specific skills can be clustered for particular levels, types, or foci of practice (Lenburg, 1999). These core competency categories collectively define practice and are applicable in multiple practice areas. Although many of them are required simultaneously in actual practice, these competencies are discrete skills than can be adapted to fit specific settings and specific practitioners (Lenburg, 1999). The essential core competencies within the model are assessment and intervention, communication, critical thinking, teaching, human caring relationships, management, leadership, and knowledge integration skills (Lenburg, 1999). Essentially all specific subskills nurses perform can be identified by one of these core competency categories.

The second question posed in the COPA Model requires that specific indicators be written to include only those behaviors, actions, or responses that are mandatory for actual practice of that competence (Lenburg, 1999). Statements should define the expected competence in clear, specific, and unambiguous terms (Lenburg, 1999). In the COPA Model, these indicators are called critical elements and are applicable to all core practice competencies. Critical elements are defined as the set of single, discrete, observable behaviors that are mandatory for the designated skill (Lenburg, 1999). The third question refers to how to implement the most effective ways for the practitioner to achieve the required competencies. The fourth, and final question, focuses on an objective performance assessment method based on established competencies. Although the final two questions are not the focus of this DNP project, the first two questions within the COPA Model have served as a guideline for developing competencies for providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. The COPA Model uses these four guiding questions to create an organizing framework of competency outcomes and performance assessment to promote competent practice.

In an effort to understand the process by which competencies can be developed, a review of the literature highlighted a number of exemplars. Baldwin, Lyon, Clark, Fulton, and Dayhoff (2007) stated when developing “practice competencies” for the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) role that practice competencies are unique to the role of the provider, that “common competencies” define the role, and “specialty practice” builds on core competencies and represents an interpretation and integration of the core competencies into the knowledge and skills of the specialty. The specific competencies for specialty practice are defined within the core competencies. Baldwin and colleagues (2007) used a descriptive survey technique to establish data on the current practice of the CNS. A survey was developed with expert input, job descriptions were elicited, feedback from membership with revisions and, with the developed competencies, made recommendations to revise the document every 5 years. Similar to the competency document developed by the RCN (2005), the competency groundwork with the CNS role was based on core competencies with specific knowledge and skills integrated into developing specific practice competencies for the CNS. In addition, Ramirez, Tart, and Malecha (2006) utilized a survey approach to collect data on the current practice among nurse practitioners in emergency care settings to develop treatment competencies for practice.

Although there are currently no competencies for botulinum toxin Type A injections and dermal fillers, there are recommendations, consensus statements, and guidelines for providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin type A injections (Carruthers, Fagiern, Matarasso, & the Botox Consensus Group, 2004; Matarasso, Carruthers, Jewell, and the Restylane Consensus Group; 2006; Shetty, 2008). A guideline, also called a protocol or standard, con- tains systematically developed statements that include recommendations, strategies, or information that assists physicians and/or other health care practitioners and patients make decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances (http://www.ahrq.gov/news/press/ngcfrpr.htm). A consensus statement or recommendation is guidance on a subject for which there is a relative deficiency of comprehensive evidence that might otherwise allow for a more definitive statement to be made (http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/25/suppl_1). A standard is an authoritative statement enunciated and promulgated by the profession, by which the quality of practice, service, or education can be judged (ASPSN, 2005). However, the scopes and standards of plastic surgical nursing are not specific to the area of practice for providers of dermal fillers or botulinum toxin Type A injections but are global to the specialty of plastic surgical nursing.

Carruthers et al. (2004) outlined recommendations for the use of botulinum toxin Type A for aesthetic enhancement. These recommendations were compiled with the latest evidence and data by members of the consensus panel. The consensus panel was compromised of expert physicians from dermatology, plastic surgery, and oculoplastic surgery. Nursing was not represented. These guidelines and recommendations presented general principles as well as specific information on the use of botulinum toxin Type A including reconstitution and handling, storage, procedural considerations such as syringe and pain management, dosing and injection site considerations, indications, patient selection, education, counseling, complications, and each anatomical site that is appropriate for treatment was presented with the sites and amount of botulinum toxin Type A to be injected (Carruthers et al., 2004). A follow-up for re-treatment was outlined as necessary in these guidelines. There was extensive information regarding anatomy of the face including muscles and muscle function. Contraindications to botulinum toxin Type A presented in the literature include injection into an area of infection or inflammation (Carruthers et al., 2004; Kane et al., 2009; Sheety, 2008). Carruthers et al., (2004) also identify pregnancy, breast-feeding, and neuromuscular function disease as contraindications. The Nurse Injector Competence Training (2009) course presents asymmetry as the most common technique related complication to botulinum toxin Type A injections. Sheety (2008) cites brow ptosis as the most common complication to treating the glabellar area. Bruising, headache, and perioral dysfunction are also presented as complications in the content of the Nurse Injector Training Course (2009). Scheduling a postprocedure follow-up was recommended (Carruthers et al., 2004). The panel members further acknowledged the proposed recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin Type A as a guideline only to help the provider ensure a satisfactory outcome (Carruthers et al., 2004). However, no specific competencies for applying the guideline were outlined.

Matarasso et al. (2006) outline recommendations for the use of Restylane (Medicis Aesthetics, Inc., Scottsdale, AZ), a widely utilized hyaluronic acid dermal filler. In this particular consensus statement of recommendations, the authors stress the importance of a complete aesthetic evaluation and a thorough understanding of the patient’s goals and preferences consistent with a realistic evaluation and recommendations (Matarasso et al., 2006). In addition, the authors emphasize that outcomes may be optimized with a treatment plan that includes patient education and assessment, adequate informed consent, and a consistent pre- and posttreatment program. In addition, the panel stresses the importance of pre- and posttreatment photographs. The informed consent process was universally recommended by the consensus panel to ensure compliance with regulatory and legal requirements as well as to manage patient expectations. The informed consent process should include product information, available alternative treatments, risk, including expected normal occurrences and possible complications, and financial responsibilities (Matarasso et al., 2006). A comprehensive treatment plan was outlined and included a patient medical history with all medications, allergies, and history of cold sores. All panel members recommended the use of ice to reduce swelling and bruising. However, most panel members did not recommen that patients self-massage (Matarasso et al., 2006). The consensus panel further outlined the various injection techniques and the facial anatomic areas appropriate for treatment that included nasolabial folds, lips, marionette lines, oral commissures, and tear troughs with special considerations for each area in recognizing, avoiding, and managing normal but unwanted posttreatment events and potential complications. The authors discussed expected problems and complications. Expected problems reported included lumps, asymmetry, over or undercorrection, needle marks, bruising, erythema, edema, and pain. Complications reported included inflammatory nodules, tyndall effect, allergic reactions, vascular occlusion, and granulomas. In summary, the authors again acknowledge these recommendations as only a consensus statement and are not intended to be a guideline document (Matarasso et al., 2006). There was no mention of the necessary competencies needed to perform these recommendations.

In a similar guideline on the use of botulinum toxin Type A, Sheety (2008) stresses the importance of patient selection, patient goals and expectations, specific treatment areas, reconstitution and handling, technique, preoperative counseling, and the informed consent process. Vedamurthy (2008) presented guidelines on the use of dermal fillers. This guideline again stresses the informed consent process, patient selection and expectations, indications, and complications. Asymmetry was presented as the most common complication of dermal fillers. Vedamurthy (2008), Sheety (2008), and Vedamurthy (2008) present these as guidelines only and specific competencies, as such, are not presented.

The Physicians Coalition for Injectable Safety has developed the Nurse Injector Competence Training (2009) course. This course was developed by a cross-specialty group consisting of the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, the American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, and the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. The coalition was founded to promote the provision and safe use of cosmetic injectables and educate the medical community. The course is taught by physicians and nurse practitioner experts in the specialty of nonsurgical facial enhancement. This is a comprehensive, introductory level course, designed for nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistant providers. The course provides a review of the treatment rationale and clinical applications for botulinum toxin Type A and a variety of Food and Drug Administration–approved hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. The importance of a thorough aesthetic analysis is examined in detail with a focus on facial anatomy including muscles, nerves, and skin layers. Effective options for pain management are presented. An opportunity to inject a skin model with dermal filler and small group discussions are also a part of this course. In addition, live patient injections with botulinum toxin Type A and hyaluronic acid fillers are demonstrated. Further discussion on patient safety and avoidance of complications is presented. The importance of teamwork, collaboration, and effective communication between the nurse/nurse practitioner/physician assistant and surgeon is highlighted. There is also an advanced course offered by this Coalition. This course provides the opportunity to review and discuss more advanced injection techniques with botulinum toxin Type A and an array of dermal fillers. Emphasis is placed on the aesthetic analysis of the aging face. Volume loss and the effects of this on facial appearance are reviewed. Live patient and video injections of volume replacement in the mid and upper face as well as contouring of the lower face are included in this course as well. Neither course outlines the specific competencies necessary for practice.

Inherently different, competencies provide the specific tools or skills needed prior to implementation of any guideline, protocol, or recommendation and are more realistic in assessing and measuring performance and are necessary to guide practice (Baldwin et al., 2007; Davies & Hughes, 2002; Finkelman & Kenner, 2009; Ramirez et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2000). Competencies can be more specific to the area of focus and in the rapidly changing healthcare delivery system, such as aesthetic medicine, require that providers possess practice-defined competencies (Zhang et al., 2000). Competencies are measureable behaviors that guide safe practice (Zhang et al., 2000). As measureable tools, competencies can be derived from an analysis of actual practice (Zhang et al., 2000). Competencies provide a venue for assessing provider performance. Competencies are used to guide practice and communicate the expectations of providers to healthcare organizations for the provision of care (Baldwin et al., 2007). Improving health care requires improved competencies in all health care professionals beginning with providing patient-centered care (Finkelman & Kenner, 2009). Competencies provide a benefit to the practitioner and enable the consistent delivery of high standards of care, ultimately benefiting the potential consumer and increasing the effectiveness of service provision (RCN, 2005). Zhang and colleagues (2001) state that competencies are important in enabling an individual to adapt to new environments and perform superior professional practice. Competencies can be observed and assessed to evaluate and measure provider performance and are different from guidelines, consensus statements, and recommendations. The necessary competencies allow guidelines, consensus statement, and recommendations to be carried out in practice. As previously stated, the guidelines, consensus statements, and recommendations presented here do not state these necessary competencies; therefore, it is fundamental to develop these necessary competencies to guide the practice of providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. The purpose of this study was to collect national data on the current practice among nursing providers within the ASPSN. The goal was to utilize the national data obtained from a survey on current practice and develop a document of the necessary competencies to guide the practice of providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections.

METHODS

This study was a cross-sectional survey that was designed to obtain national data on current practice among nursing providers within the ASPSN. In addition, multiple teaching-learning strategies designed to enhance the investigator’s knowledge in developing these competencies were also utilized including direct observation, mentoring, and role modeling. The investigator also attended a training course offered by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons and received specific training on current widely used products to perform dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections by the companies that sell the products. In addition, cadaver training was also utilized by the investigator to enhance acquisition of the technical skills necessary for performing dermal filler. The survey was approved by the Vanderbilt University institutional review board prior to dissemination to the membership of the ASPSN.

Population and Sampling

The target population was plastic surgical nurses who are currently providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. The membership of the American Society of Plastic Surgical Nursing, the professional organization for plastic surgical nurses, with more than 1,000 members, was selected to survey in order to obtain national data on current practice of nurses who provide these procedures.

Questionnaire Design

No existing instrument specific to the practice competencies of nursing providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections has been reported. In 2008, the Society of Plastic Surgical Skin Care Specialists conducted a survey of its members to quantify the characteristics and pay structures of the Society’s current and recent membership and to determine important issues facing practice and industry. This survey was structured to obtain data more specific to practice profile, work-life, and pay structure and benefits (http://www.spsscs.org/ surveyresults.ph). The Society of Plastic Surgical Skin Care Specialists is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the promotion of education, enhancement of clinical skills, and the delivery of safe, quality skin care provided to patients from the offices of plastic surgeons certified by or eligible to sit for examination by the American Board of Plastic Surgery or the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (http://www.spsscs.org/). This organization is not specific for nurses but includes cosmetologists and aestheticians as well. Therefore, a new questionnaire was created as a screening survey to obtain national data on current practice including education and training, physician supervision and collaboration, and level of education among plastic surgical nursing providers.

The fundamental knowledge of current practices among members of the ASPSN is crucial for the development of these initial competencies to guide practice as a provider of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. A survey was developed and piloted among 10 expert providers of these procedures among the membership of the ASPSN for validity of content. These 10 experts were selected because of their vast knowledge and experience within this area of practice. Revisions were made and the survey was redistributed to these same experts for validity of content. All experts validated content as appropriate to initiate the groundwork for the development of the necessary practice competencies. This resulted in a final 26-item survey. The survey questions were designed to elicit a true profile of current practice. Some questions were designed with only one specific answer such as highest level of education and others as check all that apply (see Appendix 1 for survey). Space was provided for open comments where applicable. To encourage honest reporting, confidentially was ensured and respondents were not asked any identifying information.

Data Collection and Analysis

The survey was disseminated via e-mail to the entire current membership through the National Office of the ASPSN on January 20, 2009. A description of the study was provided with the survey. The survey was disseminated a second time 2 weeks later as a reminder. The closing date of February 20, 2010, was provided on the second e-mail. Online responses for analysis were collected via the SurveyMonkey.com Web site. Descriptive statistics were utilized to report the data.

RESULTS

Response Rate and Demographics

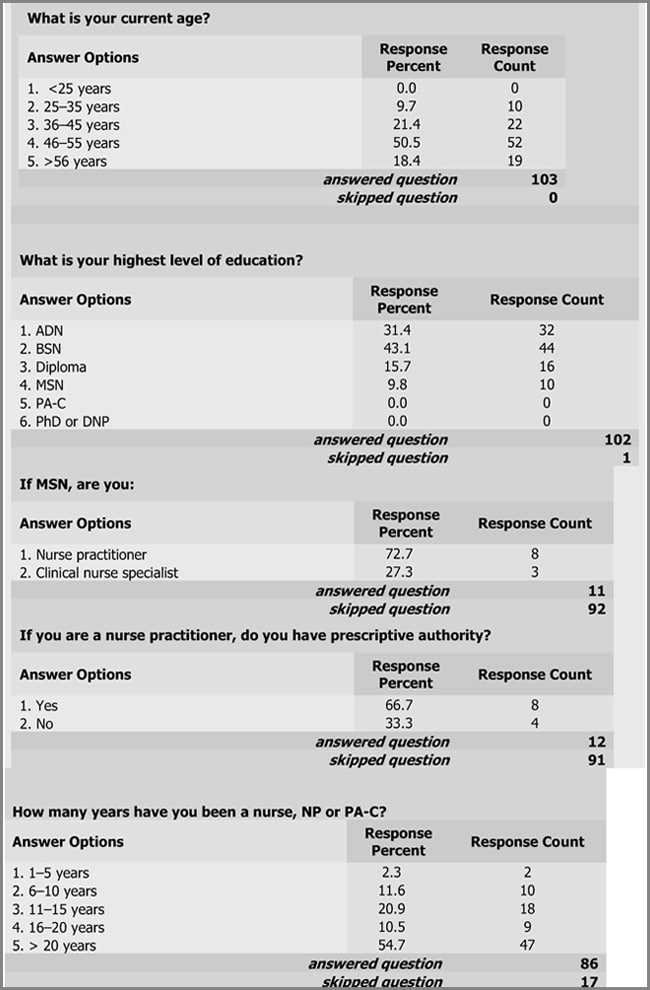

The response rate was approximately 10% of the entire membership of 1,000 (n 103). More than 50% (52/103) of the respondents were aged 46–55 years, 21.4% were 36–45 (22/103) years of age, and only 10% (10/103) of the respondents were younger than 36. Over 54% (47/86) of those responding to the survey had been a practicing nurse or nurse practitioner for over 20 years with another 21% (18/86) having a minimum of 11 years of practice. In addition, 43% of the respondents (44/104) reported having at least a baccalaureate degree in nursing. Approximately 10% (10/103) of the respondents reported having a master’s degree with the majority being nurse practitioners (73%). Approximately 67% of the nurse practitioners reported having prescriptive authority. No respondent reported having higher than a master’s level of education (see Figure 2).

Responses to Practice Items

|

| Figure 2. The majority of respondents to the survey reported being older than 36 years with the majority being between 46 and 55 years of age. Of those responding to the survey, the current educational level of most providers was a baccalaureate degree in nursing. Only 10% of the respondents reported holding a master’s degree with the greater part of these individuals being nurse practitioners. Of those respondents, none reported having higher than a master’s degree. |

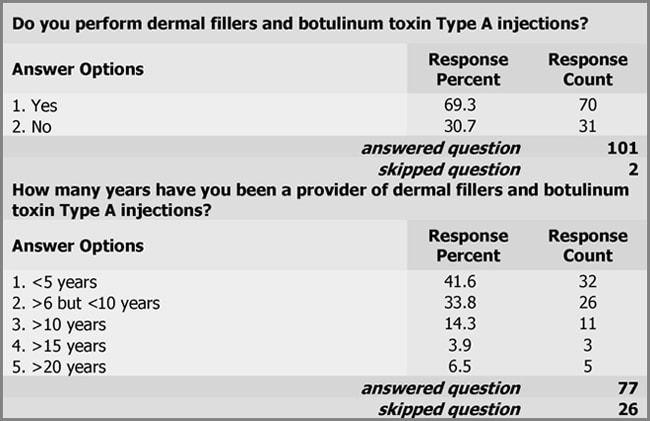

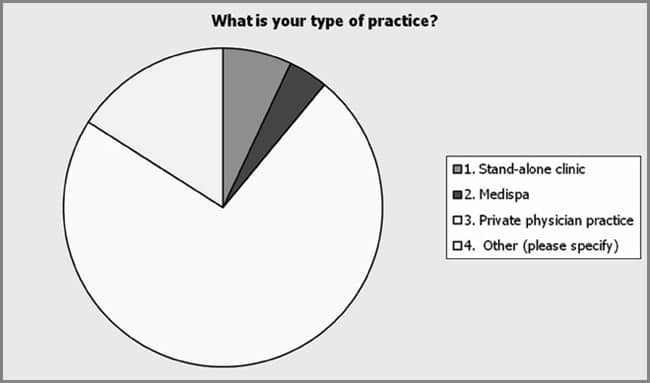

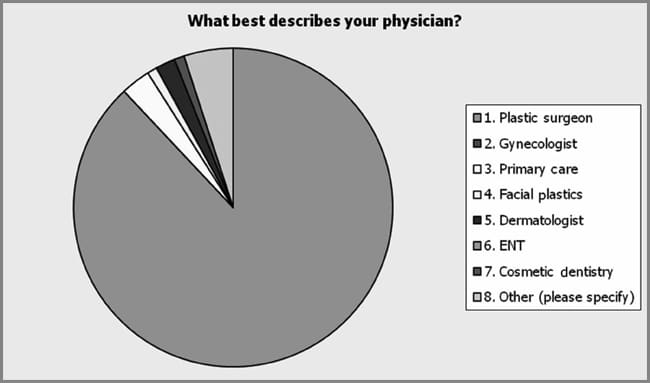

One hundred three respondents answered the survey. Eighty respondents completed the entire survey whereas others voluntarily eliminated some questions. Approximately 75% (n = 77) of those surveyed indicated that they perform dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. Of these respondents, approximately 42% (32/77) reported to have only been performing these procedures less than 5 years (see Figure 3). The majority (73%) reported their practice setting as a private physician practice. Four percent reported practicing in a medispa and 7% reported practicing in a “stand alone” clinic. Sixteen percent (16/100) reported other practice settings including a multispecialty clinic, an academic medical center, and a small nursing consulting group (see Figure 4). Only 41% of the respondents reported having a subspecialty (41/99). Specialties reported included dermatology, aging medicine, women’s health, and critical care. The remaining respondents reported affiliated specialties with plastic surgery such as certified operating room nurse and registered nurse first assistant. Collaborating physician specialty was assessed. Among the respondents, 88% (n = 100) reported that they practiced with a plastic surgeon. Only 3% of the respondents reported practicing in primary care, 2% in dermatology, 1% in both facial plastics and cosmetic dentistry. Sixteen percent of the respondents reported other collaborating physician specialties including a vascular or general surgeon and a family practice physician, and anti-aging medicine (see Figure 5).

|

| Figure 3. Approximately 69% of the respondents reported they perform dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. More than 40% (32/77) reported having performed these procedures less than 5 years with approximately 6.5% reporting performing procedures over 20 years. |

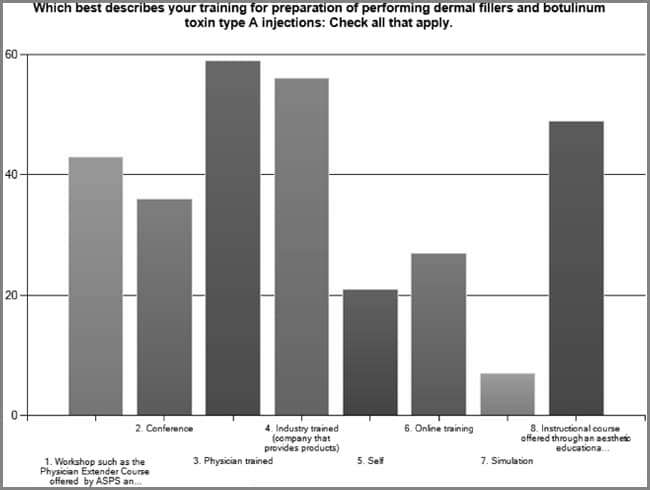

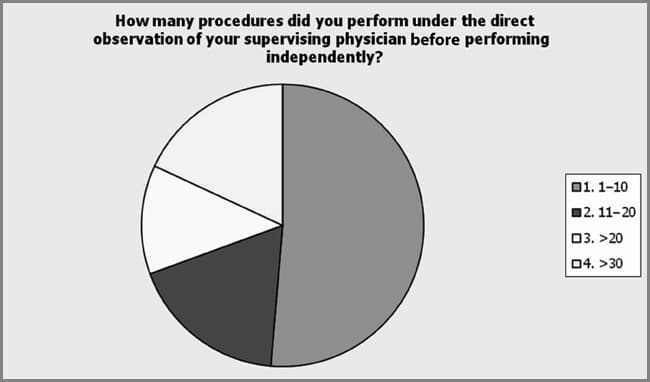

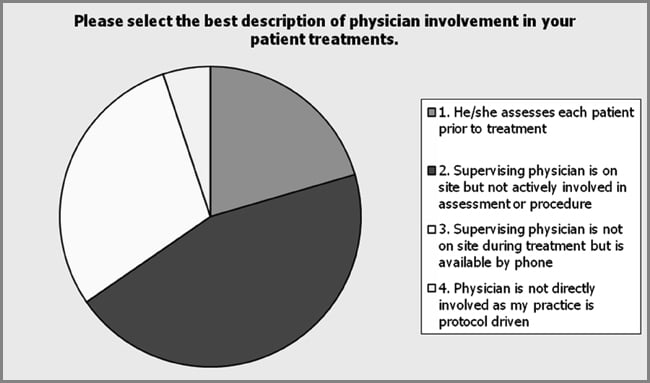

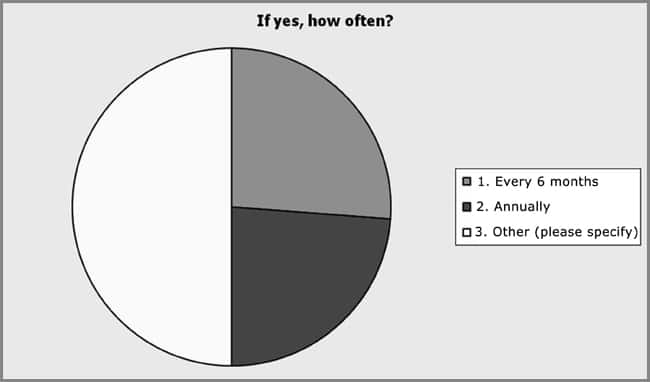

Educational preparation and training were assessed by survey and included a “check all that apply” item on the survey. Physician trained was the most popular method for acquiring the education and skills as a provider of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections, but the data show that multiple modalities were preferred (see Figure 6). This included industry training, 72.2%; aesthetic education company, 63.3%; physician extender course, 55.8%; continuing education such as conferences and workshops, 46.8%; online training, 35.1%; self-trained, 27.3%; and simulation, 9% (n = 77). The number of procedures performed under the direct supervision of a physician before practicing independently was a single answer item on the survey. The majority of respondents reported performing a minimum of 10 procedures under physician supervision before practicing independently, 12.5% of the respondents reported more than 20 with 18.1% reporting more than 20 and more than 30, respectively (see Figure 7). The continuation of physician involvement in nursing provider practice was examined by a survey item that specifically asked the level of physician involvement in their practice. There was a significant preference among respondents (44.9%) for the lack of physician’s active involvement in the assessment of the patient and performance of the procedures, but the respondents indicated that the physician was on site whereas they were performing these procedures (n = 78). Physician assessment prior to the nurse providing the procedures was reported by 20.5% of the respondents. Supervising physician not on site during assessment and performance of procedures was reported by 29.5% of the respondents and 5.1% reported their supervising physician was not involved in their practice (see Figure 8). The respondents showed no preference (57.5%) in periodic supervision of practice by their collaborating physicians (n = 42). However, of those respondents who reported that they were periodically supervised, there was no preference for time intervals between physician supervision (see Figure 9).

|

| Figure 4. Respondents (n = 100) reported a mixture of practice settings with a preference for a private physician practice (73%). Seven percent reported practicing in a “stand alone” clinic, 4% in a medispa and 16% in other settings, including university medical center, small group of nurses that practice independently and multi-specialty clinic. |

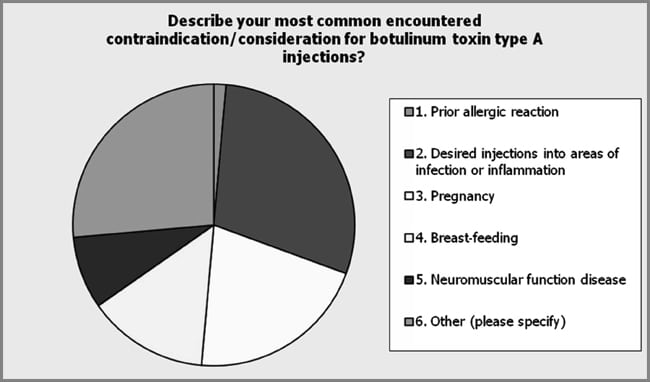

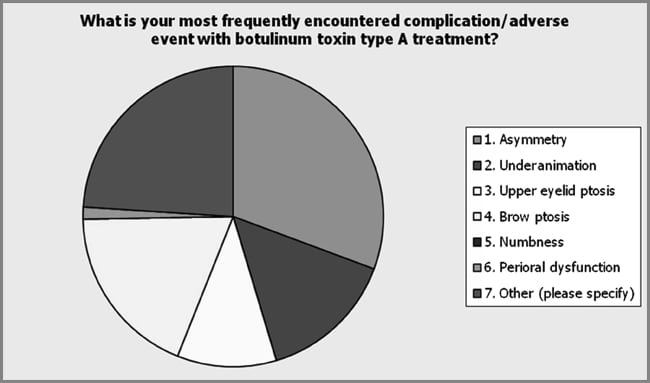

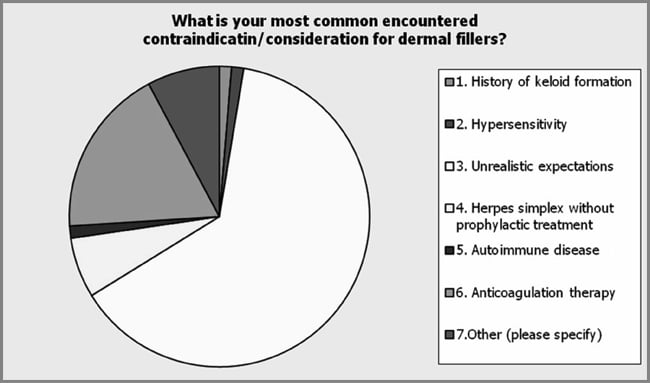

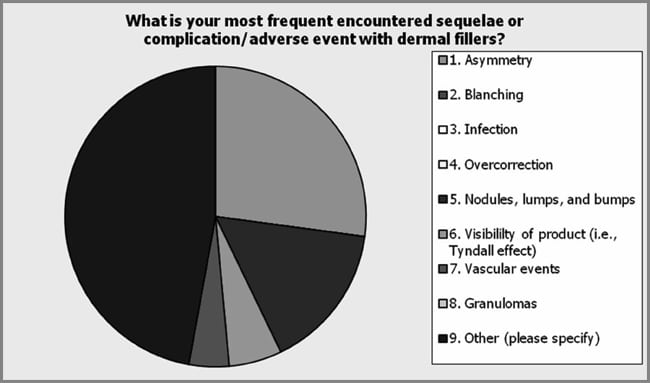

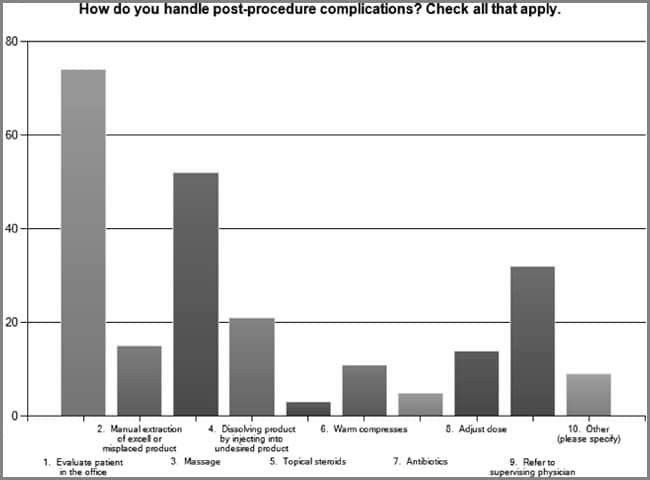

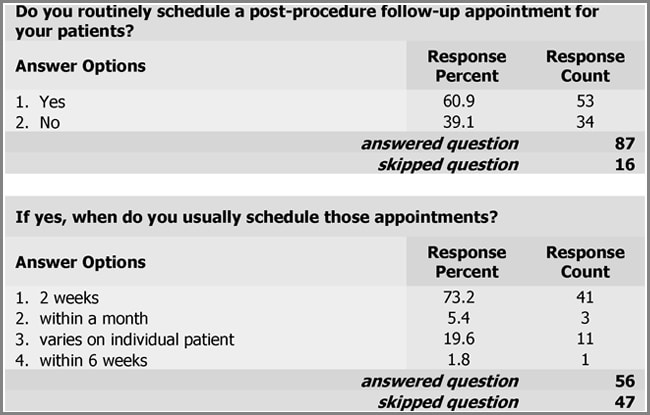

Specific provider practice was assessed including contraindications and adverse events of procedures. Among the respondents (n = 72), the potential of injecting botulinum toxin Type A into an area of infection or inflammation was the most common contraindication that the respondents identified (29.2%) (see Figure 10). Prior allergic reaction was indicated by 1.4% of the respondents (1/72), pregnancy by 20.8% (15/72), breast-feeding by 13.9% (10/72), and neuromuscular function disease by 8.3% (6/72) of the respondents. Other was indicated by 26.4% (19/72) of those responding with unrealistic expectations and the presence of brow ptosis most commonly indicated. In addition, the respondents indicated significant differences in the most common experienced complication or adverse event with botulinum toxin Type A injections (see Figure 11). Among the respondents (n = 75), asymmetry was indicated as the most common encountered complication and adverse event with botulinum toxin Type A (30.7%). Other complications indicated by the respondents included under-animation 14.7%, eyelid ptosis 10.7%, brow ptosis 18.7%, peri-oral dysfunction 1.3%, and other 24.0%. The most common other complications cited by the respondents included headache, bruising, and unrealistic expectations. Respondents were asked to provide their most common contraindication for dermal fillers. Among the respondents (n = 77), unrealistic expectations was found to be the most common contraindication to dermal fillers (63.6%; see Figure 12). Patient use of anti-coagulation therapy was the second most common contraindication (18.2%). The respondents (n = 70) indicated unrealistic expectations as the most frequently encountered complication of dermal fillers (63.6%). Other complications indicated by the respondents included asymmetry 27.1%, nodules, lumps and bumps 15.7%, and other 47.1%. Of the other category, bruising and undercorrection were most commonly cited (see Figure 13). Respondents indicated multiple modalities for treating postprocedure complications (see Figure 14). Evaluating the patient in the office was the most common method utilized by the respondents of handling postprocedure complications (92.5%). The respondents indicated massage as the second most common method to handle complications (65.0%). Other methods included referring to supervising physician (40%), dissolving product (26.3%), manual extraction of product (18.8%), warm compresses (13.8%), dose adjustment (17.5%), topical steroids (3.8%), and antibiotics (6.3%). The other category included such methods as Arnica, ice, and photo discussion with patient, nurse provider, and physician. The respondents were found to routinely schedule a postprocedure follow-up appointment (60.9%) with the majority indicating they do so within 2 weeks of the procedure (73.2%; see Figure 15).

Respondents were asked about individual malpractice coverage as a provider of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. The respondents showed no preference to carrying individual malpractice insurance with only 56.3%, indicating that they carry the insurance (49/87). Among the providers surveyed, 79.0% indicated that they have practice guidelinesn and/or protocols. In addition respondents indicated that established practice competencies are necessary (93.2%).

|

| Figure 5. Eighty-eight (n = 100) percent of the respondents reported to practicing with a plastic surgeon. Only 3% of the respondents reported practicing in primary care, 2% in dermatology, and 1% in both facial plastics and cosmetic dentistry. Sixteen percent of the respondents reported other physician specialties including vascular surgery, general surgery, family practice, and anti-aging medicine. |

|

| Figure 6. Among the respondents, physician trained was the most popular method for acquiring the education and skills as a provider of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections but the data show that multiple modalities are preferred. Although the most popular method, other learning modalities were reported; physician extender course 55.8%; continuing education such as conferences and workshops 46.8%; online training 35.1%; self-trained 27.3%; and simulation 9% (n = 77). |

|

| Figure 7. The majority of respondents reported performing a minimum of 10 procedures under physician supervision before practicing independently. A total of 12.5% of the respondents reported more than 20 with 18.1% reporting more than 20 and more than 30, respectively. |

|

| Figure 8. Physician involvement was reported by the majority (44.9%) of the respondents (n 78) as he or she was on site during the procedures but not actively involved. Physician assessment before the nurse providing the procedures was reported by 20.5% of the respondents. Supervising physician not on site during assessment and performance of procedures but was available by phone was reported by 29.5% of the respondents and 5.1% reported their supervising physician was not involved in their practice. |

|

| Figure 9. The respondents showed no preference for periodic supervision by his or her physician (57.5%). However, of those who indicated that periodic supervision was performed, there was no significant difference in the time intervals between supervision: 26.2% every 6 months, 23.8% annually, and 50% indicated other. The most common response in the other category was when the physician presence was requested. |

|

| Figure 10. The respondents indicated a preference for the most commonly encountered contraindications of botulinum toxin Type A injections (n = 72) for the desire for injections into an area of infection or inflammation (29.2%). Other contraindications indicated by respondents included Prior allergic reaction, 1.4%; pregnancy, 20.8%; breast-feeding, 13.9%; neuromuscular function disease, 8.3%; and other, 26.4%. The other category included unrealistic expectations and presence of brow ptosis. |

Other Data

The Physicians Coalition for Injectable Safety has developed the Nurse Injector Competence Training course (Nurse Injector Competence Training, 2009). This course was developed by a cross-specialty group consisting of the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, The American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, and the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. The coalition was founded to promote the provision and safe use of cosmetic injectables and educate the medical community. The course was taught by physicians and nurse practitioner experts in the specialty of nonsurgical facial enhancement. The investigator attended this course in the spring of 2009 in Las Vegas, Nevada, during the Aesthetic Symposium of the ASPSN. This was a comprehensive, introductory-level course, designed for nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistant providers. Consistent with the recommendations and consensus statements previously discussed, the course provided a review of the treatment rationale botulinum toxin Type A and a variety of Food and Drug Administration–approved hylauronic acid dermal fillers and was selected as a method of training by 55.8% of the nursing providers surveyed. The importance of a thorough aesthetic analysis was examined in detail with a focus on facial anatomy including muscles, nerves, and skin layers, consistent with the published recommendations and consensus statements. Effective options for pain management were presented. There was also an opportunity for the investigator to inject a skin model with filler and attend small group discussions. In addition, live patient injections with botulinum toxin Type A and hyaluronic acid fillers were demonstrated. A discussion on patient safety was presented with an emphasis on avoiding complications. The course also reviewed the importance of teamwork, collaboration, and effective communication between the nurse/nurse practitioner/physician assistant and surgeon. The importance of how this relationship can have a positive economic impact on the plastic surgery practice was also discussed.

|

| Figure 11. Asymmetry was reported as the most frequently encountered complication after botulinum toxin Type A injections. The other category was the second most common complications reported by the respondents with bruising and unrealistic expectations most often cited. |

|

| Figure 12. The respondents showed a preference in identifying the most common contraindication to dermal fillers. Unrealistic expectation was the most frequent cited by 49 (63.6%) of 77 respondents. The second most common contraindication was patient use of anti-coagulation therapy including aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. |

|

| Figure 13. Among the respondents, the other category was indicated as the most common complication of dermal fillers. The most common complications cited in this category included bruising and undercorrection. Other complications indicated by the respondents included asymmetry, 27.1%; nodules, lumps, and bumps, 15.7%; and other, 47.1%. |

|

| Figure 14. Evaluating the patient in the office was the most common method utilized by the respondents of handling postprocedure complications (92.5%). The respondents indicated massage as the second most common method to handle complications (65.0%). Other methods included referring to supervising physician (40%), dissolving product (26.3%), manual extraction of product (18.8%), warm compresses (13.8%), adjust dose (17.5%), topical steroids (3.8%), and antibiotics (6.3%). The other category included such methods as Arnica, ice, and photo discussion with patient, nurse provider, and physician. |

In addition to the survey and Nurse Injector Competence Training, the investigator utilized direct observation of the performance of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections by the collaborating physician as well as by other plastic surgeons in the practice. Industry training for specific products for enhancement was also utilized. Skill acquisition and anatomy were enhanced with cadaver training.

|

| Figure 15. The current practice among nursing providers surveyed is to schedule a postprocedure follow-up appointment within 2 weeks of the procedure. |

DISCUSSION

Among the 103 nursing providers who responded to the survey, there were common core issues that became apparent. This included contraindications for the use of botulinum toxin Type A and dermal fillers, postprocedure complications that may occur as well as strategies in terms of managing complications. The data also revealed that there is no common method that providers are taught to assess the aesthetic patient, confirm contraindications, injection techniques, or identifying or managing complications. Based on the data presented, there is a lack of a collaborative relationship in current practice among nursing providers. In addition, there is variability in terms of patient follow-up and practitioner certification. While no specific guidelines or recommendations exist within the American Society of Plastic Surgical Nursing, the nursing providers responding to this survey responded affirmatively that they felt that competencies to guide practice as providers are necessary (93.2%).

While it should be noted that there are limitations of this study, including the fact that only 10% of the organization responded to the questionnaire, the need for competencies is apparent. In addition to the small sample size, the investigator acknowledges that this project focused only on surveying one nursing specialty, plastic surgical nursing. Nursing providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections practice in other nursing specialties, such as dermatology, and surveying these providers could produce supportive or conflicting data. Another limitation of this DNP project is the fact that there was not a survey item that directly assessed the content of the informed consent process utilized by these nursing providers. In addition, this could have highlighted data more directly on patient assessment and selection as well as risks, benefits and complications. Although not directly assessed, patient selection for applicability of treatment could have been more accurately evaluated including the aging process.

Based on the review of the literature, there are no widely accepted and utilized competencies to guide the practice of providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. Guidelines, recommendations, and consensus statements have been developed but lack identification of the necessary competencies for practice. Qualitative data from a national survey supports that those responding feel competencies are needed. Core issues encountered by all respondents in practice became apparent. Also, the process by which one becomes competent as a provider is highly variable; hence, the need for competencies.

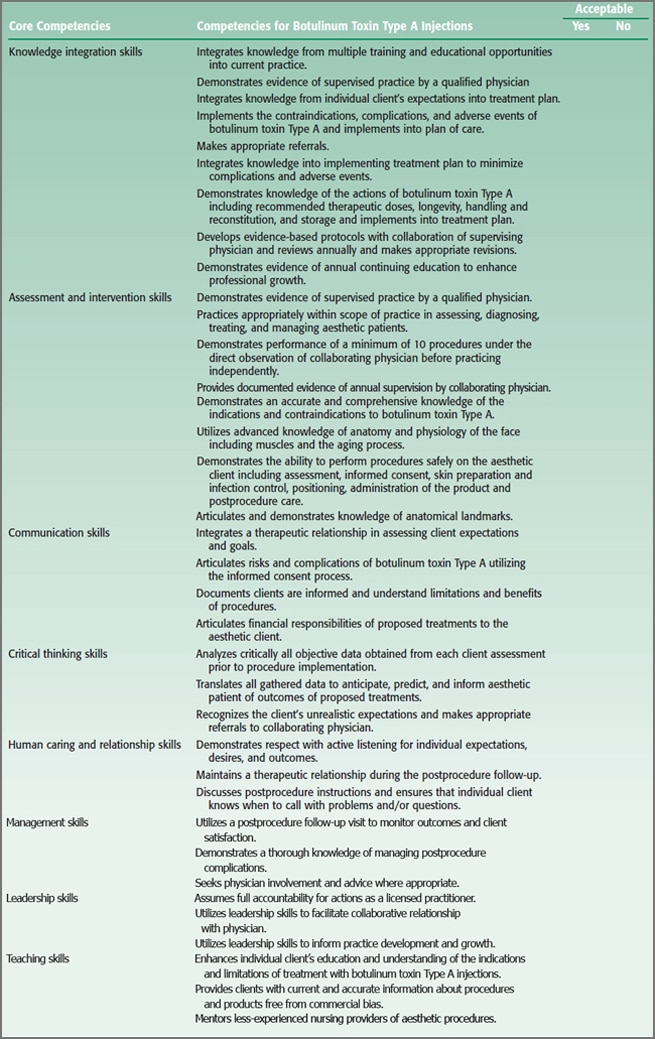

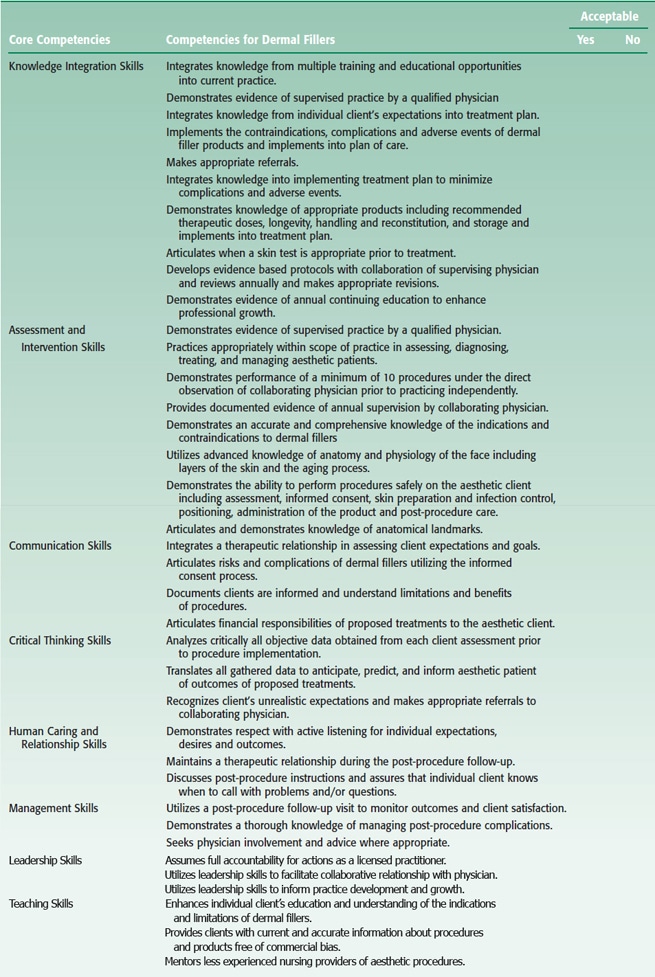

The proposed necessary competencies for providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections are presented in Tables 1 and 2. These proposed competencies are based on the framework, concepts, and methods of the COPA Model as the theoretical framework for this scholarly project. The basic organizing framework for the COPA Model is simple but comprehensive and may be used in education as well as program development and practice settings (Lenburg, 1999). This conceptual framework facilitated and directed the development of the proposed necessary competencies for this DNP project. The COPA Model consists of eight core practice competencies under which an array of specific skills to define each competency for a particular practice can be clustered (Lenburg, 1999). Utilizing the COPA Model and the eight core competencies, the proposed competency document was developed and identified evidencebased skills, knowledge, and behaviors necessary for providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin type A injections. The eight core competencies of the COPA model are listed with identified specialty competencies for providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections (Tables 1 and 2).

The first core competency is knowledge integration skills. Based on a review of the literature, appropriate training is fundamental for practice (Carruthers et al., 2004; Matarasso et al. 2006; RCN, 2005; Shetty, 2008). While no formal training exists for aesthetic providers, these data support the use of multiple learning modalities by nursing providers. Integrating this knowledge into skills as a provider of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A includes a thorough understanding of indications, complications, adverse events, and contraindications along with a broad knowledge of products utilized for nonsurgical facial enhancement (Carruthers et al., 2004; Matarasso et al., 2006; RCN, 2005, Shetty, 2008). These data presented in this DNP project support the early identification and management of complications using multiple techniques. Congruent with the evidence cited, these data also support using a postprocedure follow-up visit to monitor outcomes or have the patient call and/or return to the office for evaluation (Carruthers et al., 2004; Matarasso et al., 2006; RCN, 2005; Shetty, 2008). Collaborative practice was inconsistent with the findings from this DNP project, but the data support the use of protocols. According to Jones (2009) and the Nurse Injector Training Course (2009), a collaborative practice is essential and practice should be within the individual’s scope of practice. Periodic supervision by the collaborating physician was supported by the data of this project.

The second core competency is assessment and intervention skills. These data support the performance of a minimum of 10 procedures under supervision before practicing independently. This is consistent with the recommendation of the Nurse Injector Training Course (2009). Patient assessment with the knowledge of advanced anatomy of the skin, muscles, and aging process was included in the recommendations, guidelines, consensus statement, and competency document presented (Carruthers et al., 2006; Matarasso et al., 2006; Royal College of Nursing, 2005; Shetty, 2008).

TABLE 1 The Competency Outcomes and Performance Assessment (COPA) Model (Lenberg, 1999) serves as the theoretical framework for this proposed document compiling the necessary competencies for providers of botulinim toxin Type A injections

An honest, respectful, and caring relationship with attention to active listening to the aesthetic patient’s goals, expectations, and desired outcomes is essential to patient satisfaction (Carruthers et al., 2004; Matarasso et al., 2006; RCN, 2005; Shetty, 2008). This subset of skills is included in the core competency of communication skills. An unrealistic expectation was the most common cited complication from dermal fillers by the respondents in this project, consistent with other authors in the literature (Matarasso et al., 2006; Shetty, 2008). This validates the necessity of honest, open communication included in the informed consent process and recognizing patient goals and desires that are not attainable.

In the fourth core competency, critical thinking skills are included. All gathered data, both objective and subjective, must be integrated into the treatment plan (RCN, 2005; Shetty, 2008). Many respondents indicated their collaborating physician was not on site at the time of assessment and performance of these procedures. The nursing provider must be competent in the skills required to adequately assess the aesthetic patient, utilize the knowledge of anatomy and the aging process, anticipate complications, and refer the patient to the collaborating physician in the event that patient goals and expectations are unrealistic.

Human caring and relationship skill compromises the fifth core competency within the model. According to the data presented in this project, evaluating the patient in the office was the most common way to handle postprocedure complications. This portrays caring and fosters a therapeutic relationship among the provider and the patient. This relationship must be initiated with respect for individual goals and expectations during the initial consultation and continue through and after the treatment (Carruthers et al., 2004; Matarasso et al., 2006; Shetty, 2008).

Management skills is another core competency within the model that directed the development of the subset of specialized skills necessary for providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections. The provider utilizes a postprocedure encounter to assess and manage outcomes. These data support nursing providers within the ASPSN have the necessary knowledge to manage complications and demonstrate appropriate involvement of their collaborating physician. The Nurse Injector Training Course (2009) stresses the importance of the early recognition of complications and management with physician involvement and how this involvement fosters that relationship.

Leadership and teaching skills compromise the last of the two core competencies within the COPA Model. Practice protocols and guidelines were found to be used in practice by nursing providers surveyed. Other guidelines and protocols for providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A exist in the literature (Carruthers et al., 2004; Matarasso, Carruthers, Jewell, and the Restylane Consensus Group, 2006; Shetty, 2008).

TABLE 2 The Competency Outcomes and Performance Assessment (COPA) Model (Lenberg, 1999) serves as the theoretical framework for this proposed document compiling the necessary competencies for providers of dermal fillers injection

Leadership skills can be utilized in the facilitation of a collaborative relationship with a physician in the development of protocols and inform practice development and growth based on this expertise. Teaching skills are apparent in patient assessment as patient education can enhance understanding of indications and limitations and provide current and accurate information about procedures and products (Carruthers et al., 2004; Matarasso et al., 2006; Shetty, 2008).

These competency documents were developed on the basis of national data, review of the literature, and other modalities for data collection as previously described. These competency documents are to serve as a practice guide for the provider of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections to assess and measure performance and provide a foundation for safe and effective practice.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The current practice among nursing providers necessitates further evaluation. This investigator recommends annually evaluating the practice of plastic surgical nursing providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A injections as these current data utilized in the development of the proposed competencies only present the groundwork for current practice. After dissemination, it will be imperative that the impact of these developed competencies on practice of both registered nurses and advanced practice nurses as providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A be assessed. It will also be necessary to evaluate and revise this document as technology changes and new products are introduced. Changes in current practice may also be implicated in the revisions of the proposed document.

CONCLUSION

Most providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin Type A remain nurses. It is essential that competencies are developed to assess and evaluate the quality of current practice to protect both the consumer and the provider. Guidelines and recommendations do not fulfill this requirement; therefore, it is necessary that competencies be developed and updated and remain current for this rapidly growing area of practice. The intentional use of this proposed competency document is to promote safe, effective, and quality practice among nursing providers.

REFERENCES

- AHCPR Invites Clinical Practice Guidelines for Public/Private National Guideline Clearinghouse (1998). Retrieved September 26, 2009, from http://www.ahrq.gov/news/press/ngcfrpr.htm

- American Society of Plastic Surgical Nurses. (2005). Plastic surgical nursing scope and standards of practice. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association.

- Baldwin, K., Lyon, B., Clark, A., Fulton, J. & Dayhoff, N. (2007). Developing clinical nurse specialist practice competencies. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 21(6), 297–303.

- Carruthers, J., Fagiern, S., Matarasso, S., & the Botox Consensus Group. (2004). Consensus recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin type A in facial aesthetics. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 114(6 S), 1S–22S.

- Core competencies (2006). Retrieved March 31, 2010, from http://www.ehow.com/list_6099114_core-competencies-nursing. html.

- Davies, B., & Hughes, A. (2002) Clarification of advanced nursing practice: Characteristics and competencies. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 16(3), 147–152.

- Diabetes Care Consensus Statements (2002). Retrieved September 26, 2009, http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/25/suppl_1

- Finkelman, A., & Kenner, C. (2009). Professional nursing concepts competencies for quality leadership. Sudbury, MA: Jones Bartlett.

- Jones, B. (2009). Medical aesthetics: A growing practice specialty for NPs. Advances for Nurse Practitioners. Retrieved June 6, 2009, from http://nursepractitioners.advanceweb. com/Editorial/Content/editorial aspx?CC=81797

- Kane, M., Brandt, F., Rohrich, R., Narins, R., Monheit, G., Huber, M., & the Reloxin Investigational Group. (2009). Evaluation of variable-dose treatment with a new U.S botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) for correction of moderate to severe glabellar lines: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 124 (5), 1619–1629

- Kilbourne, J.(2006). Sociology of advertising and the stereotyping of women in the media gender roles, personal dissatisfaction and issues of patriarchy—who is really to blame? Retrieved August 31, 2009, from http://www.cheathouse.com/essay/essay_view.php?p_essay_id=70530

- Kohn, L., Corrigan, J., & Donaldson, M. (Eds.). (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine.

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons. (2009). Report of the 2008 Statistics National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Statistics. Retrieved August 29, 2009, from http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Media/Statistics.html.

- Lenburg, C. (1999). The framework, concepts and methods of the competency outcomes and performance assessment (COPA) mode. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 4(2). Retrieved May 18, 2009, from http://www.nursingworld.org/

- Lenburg, C. (2008). The influence of contemporary trends and issues on nursing education. In B. Cherry & S. Jacob (Eds.), Contemporary nursing issues, trends, and management (pp. 43–70). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby.

- Lenburg, C., Klein, C., Asdur-Rahman, V., Spencer, T., & Boyer, S. (2009). A comprehensive framework designed to promote quality care and competence for patient safety. Nursing Education Perspectives, 30(5), 312–317.

- Maier, K. (1998). Core competencies for nursing. Retrieved March 30, 2010, from http://www.ehow.com/list_6099114_core- competencies-nursing.html.

- Matarasso, S., Carruthers, J., Jewell, M., & the Restylane Consensus Group. (2006). Consensus recommendations for soft-tissue augmentation with nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (Restylane). Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 117(3S), 3S–34S.

- Nurse Injector Competence Training. (2009). Physician’s coalition of injectable safety. Garden Grove, CA: American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery.

- Ramirez, E., Tart, K., & Malecha, A. (2006). Developing nurse practitioner treatment competencies in emergency care settings. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 28(4), 346–359.

- American Society of Plastic Surgical Nurses. (1989) Plastic surgical nursing certification. Retrieved March 15, 2010, from https://www.aspsn.org/certification.html. Pensacola, FL: Author

- Royal College of Nursing. (2005). Aesthetic nursing RCN guidance on best practice: Retrieved September 25, 2009, from http://www.rcn.org/

- Shetty, M. (2008). Guidelines on the use of botulinum toxin type A. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venerologist and Leprologists, 74, S13–S22.

- Society of Plastic Surgical Skin Care Specialists. 2009. Membership practice profile survey. Retrieved March 1, 2010, from http://www.spsscs.org/

- Society of Plastic Surgical Skin Care Specialists. 2008 practice profile survey executive summary. Retrieved March 1, 2010, from http://www.spsscs.org/surveyresults.php.

- Vedamurthy, M. (2008). Standard guidelines for the use of dermal fillers. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venerologist and Leprologists, 75, S23–S27.

- Zhang, Z., Luk, W., Arthur, D., & Wong, T. (2000). Nursing competencies: Personal characteristics contributing to effective nursing performance. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(4), 467–474.

APPENDIX 1

Project Survey

Dear Nursing Colleague:

My name is Marcia Spear and this study is part of a requirement for completion of a Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) degree at Vanderbilt University School of Nursing. I am conducting a clinical study for my degree project and I am requesting your participation.

The Title of the Study is: What Are the Practice Necessary Competencies to Perform Dermal Fillers and Botulinum Toxin Type A Injections?

The Purpose of the Study is: to establish the competencies required for providers to possess in order to perform dermal fillers and botulinum toxin type A injections.

Your Participation would help develop competencies for future health care providers of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin type A injections. You will be asked to complete a short survey, which includes demographics, and will take less than 10 min to complete. You can quit at any time and don’t have to answer any questions that you don’t want to. The survey is anonymous and will not contain any identifying information. All efforts, within reason, will be made to keep your completed survey confidential but total confidentiality cannot be guaranteed.

Your participation is completely voluntary and you may withdraw at any time during the study. I would appreciate a copy of any protocols that you might have developed for your practice. Please let me know if you wish to have the results of this survey.

Your confidentiality will be protected. The survey is anonymous and will not contain any identifying information. All efforts, within reason, will be made to keep your completed survey confidential but total confidentiality cannot be guaranteed.

For additional information about giving consent or your rights as a participant in this study, please feel free to contact the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board Office at (615) 322-2918 or toll free at (866) 224-8273.

For questions, concerns and/or a copy of the results sent to you, please contact:

Marcia Spear/Clinician of Study

Phone (615)343-8426

E-Mail: marcia.spear@vanderbilt.edu

1. What is your current age?

- <25 years

- 25–35 years

- 36–45 years

- 46–55 years

- >56 years

2. What is your highest level of education?

- ADN

- BSN

- Diploma

- MSN

- PA-C

- PhD or DNP

3. If MSN, are you

- nurse practitioner?

- clinical nurse specialist?

4. If you are a nurse practitioner, do you have prescriptive authority?

- Yes

- No

5. How many years have you been a nurse, NP or PA-C?

- 1–5 years

- 6–10 years

- 11–15 years

- 16–20 years

- >20 years

6. Do you perform dermal fillers and botulinum toxin type A injections?

- Yes

- No

7. How many years have you been a provider of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin type A injections?

- <5 years

- >6 but <10 years

- >10 years

- >15 years

- >20 years

8.What is your type of practice?

- Stand-alone clinic

- Medispa

- Private physician practice

- Other (please specify)

9.Do you have a subspecialty?

- Yes

- No

10.If the answer to the above question is yes, please specify.

- Family practice

- Gerontology

- Women’s Health/Gynecology

- Cardiology

- Emergency

- Other (please specify)

11. Which best describes your training for preparation of performing dermal fillers and botulinum toxin type A injections: Check all that apply.

- Workshop such as the Physician Extender Course offered by ASPS and ASAPS

- Conference

- Physician trained

- Industry trained (company that provides products)

- Self

- Online training

- Simulation

- Instructional course offered through an aesthetic educational company

12. How many procedures did you perform under the direct observation of your supervising physician before performing independently?

- 1–10

- 11–20

- >20

- >30

13. Please select the best description of physician involvement in your patient treatments.

- He/she assesses each patient prior to treatment

- Supervising physician is on site but not actively involved in assessment or procedure

- Supervising physician is not on site during treatment but is available by phone

- Physician is not directly involved as my practice is protocol driven

14. What best describes your physician?

- Plastic surgeon

- Gynecologist

- Primary care

- Facial plastics

- Dermatologist

- ENT

- Cosmetic dentistry

- Other (please specify)

15. Describe your most common encountered contraindication/consideration for botulinum toxin type A injections?

- Prior allergic reaction

- Desired injections into areas of infection or inflammation

- Pregnancy

- Breast-feeding

- Neuromuscular function disease

- Other (please specify)

16. What is your most frequently encountered complication/adverse event with botulinum toxin type A treatment?

- Asymmetry

- Under-animation

- Upper eyelid ptosis

- Brow ptosis

- Numbness

- Perioral dysfunction

- Other (please specify)

17. What is your most common encountered contraindication/consideration for dermal fillers?

- History of keloid formation

- Hypersensitivity

- Unrealistic expectations

- Herpes simplex without prophylactic treatment

- Auto-immune disease

- Anticoagulation therapy

- Other (please specify)

18. What is your most frequent encountered sequelae or complication/adverse event with dermal fillers?

- Asymmetry

- Blanching

- Infection

- Overcorrection

- Overcorrection

- Visibility of product (i.e., Tyndall effect)

- Vascular events

- Granulomas

- Other (please specify)

19. How do you handle postprocedure complications? Check all that apply.

- Evaluate patient in the office

- Manual extraction of excell or misplaced product

- Massage

- Dissolving product by injecting into undesired product

- Topical steroids

- Warm compresses

- Antibiotics

- Adjust dose

- Refer to supervising physician

- Other (please specify)

20. Do you routinely schedule a postprocedure follow-up appointment for your patients?

- Yes

- No

21. If yes, when do you usually schedule those appointments?

- 2 weeks

- within a month

- varies on individual patient

- within 6 weeks

22. Are you periodically supervised by your collaborating/supervising physician?

- Yes

- No

23. If yes, how often?

- every 6 months

- annually

- Other (please specify)

24. Do you carry individual malpractice insurance?

- Yes

- No

25. Do you have practice protocols or guidelines for dermal fillers and/or botulinum toxin Type A injections?

- Yes

- No

26. Do you think having established competencies to guide practice as provider of dermal fillers and botulinum toxin type A injections are necessary?

- Yes

- No

Thank you for your time in filling out this survey. Your information is appreciated.